Editor's Note:

In the early hours of January 3, 2025, the U.S. military conducted airstrikes on Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, and other locations, subsequently seizing President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, and transporting them to New York City to await judicial trial. This operation resulted in explosions and at least dozens of casualties within Venezuelan territory, with the U.S. side stating it would not rule out further military intervention. Donald Trump expressed that the U.S. would temporarily "take over" Venezuela until a "secure transition" is achieved and encouraged large U.S. oil companies to enter the country. The Venezuelan government condemned this as "military aggression," and Vice President Delcy Rodríguez was designated as the acting president, refusing to cooperate with the U.S. actions.

Professor Zheng Ge of the KoGuan School of Law at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, a guest at the Global South Academic Forum (2025), has authored an article analyzing how the United States utilizes legal interpretation techniques to blur the boundaries between war and law enforcement. He points out that the U.S. transforms external military interventions into law enforcement operations through domestic law, downgrading heads of sovereign states to criminal suspects to circumvent the constraints of international law. This practice originates from the COIN (Counterinsurgency) law system developed since the U.S. War on Terror, which, through the unilateral expansion of judicial jurisdiction, essentially establishes a U.S.-centered order of legal imperialism and thoroughly undermines the principle of sovereign equality in international law.

This article was originally published on Professor Zheng Ge's personal public account and is now reprinted in full with authorization.

On January 3, 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump claimed that the U.S. had successfully "captured" Venezuelan President Maduro and his wife, removing them from Venezuela. Subsequently, U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi announced on social media that the sitting President of Venezuela, Maduro, and his wife had been indicted in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The peculiar aspect of this news lies not in the indictment itself—as the U.S. judicial system's in absentia indictment of foreign political figures is no longer novel—but in Bondi's deliberate omission of Maduro's presidential title, characterizing him instead as a suspect in a "narcoterrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy, and possession of machine guns and destructive devices." This seemingly technical choice of nomenclature actually reveals a deeper structural issue within the operation of the U.S. legal system: in American legal discourse, when can the legitimate head of a sovereign state be stripped of their political identity and instead be subjected to the jurisdiction of U.S. domestic courts as an ordinary criminal? The answer to this question is precisely hidden within the legal techniques developed by the United States since the September 11 attacks, which transform external military interventions into domestic law enforcement operations.

Image Captions: Venezuelan citizens take to the streets to condemn the U.S. military operations against Venezuela. Source: TeleSur.

To comprehend the legal essence of the Maduro case, one must first understand how the United States has reconstructed the boundaries between "war" and "law enforcement" through legal interpretation techniques. Traditional international law is built upon the principle of sovereign equality within the Westphalian system, where armed conflicts between states are strictly governed by Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the UN (United Nations) Charter, allowing the use of force only with Security Council authorization or in response to an armed attack. However, since the passage of the 2001 AUMF (Authorization for Use of Military Force), the U.S. executive branch, through a series of legal memorandums and opinions from the DOJ (Department of Justice) OLA (Office of Legal Counsel), has systematically redefined certain cross-border military actions as "law enforcement pursuits" rather than traditional war. The core of this transformation lies in the creative expansion of the concept of "insurgency": while traditional international law defines insurgency as a challenge by domestic armed forces against their own government, U.S. legal rhetoric extends it to "challenges by transnational non-state actors against the international order," thereby allowing the U.S. to position itself as a law enforcement force "invited to assist in counterinsurgency" rather than a belligerent party launching an aggressive war.

This image shows a slide from the "Constitutional Law" and "Law and Development" courses I have taught since 2017. My American doctoral student, Ben Liu, first alerted me to the U.S. Counterinsurgency Law. This is not a specific branch of law but a theoretical description of the U.S. "foreign-related rule of law." There are many laws in U.S. domestic law targeting other sovereign states and their regions. According to these laws, the legitimate governments of other sovereign states are sometimes labeled as "insurgents," while at other times, rebels in other countries may be designated as "insurgents," demonstrating that the order disrupted by these "insurgents" is not the domestic order of a specific sovereign state, but the global order dominated by the United States.

The cunning nature of this legal logic is that it creates a "hybrid legal state": it invokes certain rules of the law of armed conflict to justify the use of lethal force, while applying more flexible law enforcement standards regarding jurisdiction, detention procedures, and target review. The 2012 revision of the U.S. Department of Defense Counterinsurgency Manual blurred the line between "counterinsurgency" and "overseas stability operations" for the first time, redefining U.S. military support for foreign governments to suppress "insurgencies" as "law enforcement assistance." Under this framework, the United States does not need to declare war on Venezuela, nor does it need to treat the Maduro government as a belligerent adversary; it only needs to designate specific individuals as "members of an international criminal network" through the "threat assessment" process in the President’s Daily Brief. Once this legal characterization is complete, the entire operation slides from the framework of international law into the jurisdiction of U.S. domestic criminal law. Maduro is no longer a sovereign head of state but a "fugitive felon," a criminal suspect who can be globally pursued, extradited, and tried in a U.S. court.

The historical origins of this legal transformation can be traced back to the Piracy Act of 1806. This act empowered the U.S. President to authorize naval officers to "arrest, seize, and deliver" pirates on the high seas, while modern legal interpretation replaces the concept of "pirate" with "international terrorist" or "head of a transnational criminal organization," and "high seas" with "ungoverned spaces." In the 2011 Al-Aulaqi v. Panetta case, the U.S. government successfully invoked this logic to conduct a drone strike against a U.S. citizen in Yemen, justifying it as "law enforcement assistance" at the invitation of the Yemeni government and thus applying "evading judicial jurisdiction" rules. Although the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that the plaintiff lacked standing, it tacitly accepted the government’s legal framework in its incidental opinions—namely, that as long as an operation is packaged as a counterterrorism pursuit of a non-state actor, it does not trigger the reporting obligations of the War Powers Resolution. This ruling essentially transformed overseas military operations into "law enforcement" under a domestic legal framework, providing a legal precedent for subsequent cross-border capture operations.

In the Maduro case, the four charges cited by the U.S. Department of Justice—narcoterrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy, possession of machine guns and destructive devices, and conspiracy to possess machine guns and destructive devices directed at the United States—all fall under domestic criminal offenses stipulated in Title 18 and Title 21 of the U.S. Code (18 U.S.C. and 21 U.S.C.). This means that the jurisdictional basis claimed by the U.S. court is not any international treaty or UN authorization, but purely the unilateral expansion of "extraterritorial jurisdiction" by U.S. domestic legislation. According to the "effects principle" and "protective principle" developed in U.S. legal practice, as long as criminal acts have a substantial impact on U.S. territory or citizens, or threaten U.S. security interests, U.S. courts can exercise jurisdiction regardless of the actor's nationality or the location of the act. This jurisdictional claim received partial support from the Supreme Court in the 1990 case United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, which clearly stated that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to searches of non-resident aliens abroad. Furthermore, in an undisclosed 2010 memorandum, the DOJ Office of Legal Counsel systematically elaborated on the logic of transforming the right of "active self-defense" into domestic law: converting the right of self-defense from a single-event response into the "systematic elimination of a continuous-threat entity," and analogizing it to police actions against a "continuous criminal organization."

The operation of this legal architecture relies on a key conceptual shift: redefining a sovereign state government as an "insurgent organization." In traditional international law discourse, the criterion for determining the legitimacy of a regime is the "effective control principle"—as long as the regime can effectively control territory, maintain basic order, and fulfill international obligations, it should be recognized as the legitimate government of that country. However, the U.S. counterinsurgency law logic introduces a brand-new standard: "whether it conforms to the legitimate norms of the international order." The ambiguity of this standard lies in the fact that the so-called "legitimate norms of the international order" have no objective definition in international law and depend entirely on the American political elite's imagination of the global order. In this imagination, the world is divided into "responsible stakeholders" and "rogue states"; the former comply with the international rules dominated and formulated by the United States, while the latter are "insurgents" against this order. Once a regime is labeled a "rogue state," it is no longer viewed as a legitimate member of the system of sovereign equality but is downgraded to an insurgent force that needs to be "pacified."

The danger of this legal discourse is that it completely inverts the basic logic of international law. In the Westphalian system, sovereignty is a legal status that does not change based on the nature or policies of a regime. A country can be morally condemned, diplomatically isolated, and economically sanctioned, but its sovereign status itself is inalienable. However, the U.S. counterinsurgency law logic transforms sovereignty into a privilege that can be granted or revoked, with criteria determined unilaterally by the United States. Venezuela is undoubtedly a sovereign state in the sense of international law, and Maduro was elected and re-elected president multiple times through constitutional procedures; the regime is recognized by UN membership and maintains diplomatic relations with the vast majority of countries in the world. Yet, in the U.S. legal narrative, these facts become irrelevant. The Maduro government is characterized as a "criminal syndicate," and its rule over Venezuela is described as an "illegal occupation," making the capture of Maduro not an infringement on a sovereign head of state, but a legitimate pursuit of a "transnational criminal organization leader."

The legal consequences of such a characterization are extremely far-reaching. Once Maduro is successfully arrested and transferred to U.S. judicial jurisdiction, he will not enjoy any head-of-state immunity or prisoner-of-war status, but will instead face trial as an ordinary criminal defendant. U.S. courts will invoke the principle that "head-of-state immunity does not apply to international crimes," but the problem is that the crimes Maduro is charged with are not war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide in the sense of international law, but purely U.S. domestic criminal law offenses. This means that U.S. courts are effectively asserting that as long as U.S. domestic law defines an act as a crime and determines that the act threatens U.S. interests, the United States can exercise criminal jurisdiction over anyone, anywhere in the world—including heads of sovereign states. The absurdity of this claim is that it renders a series of fundamental principles in international law—such as sovereign immunity, non-interference in internal affairs, and diplomatic relations—completely meaningless. If every country could unilaterally define crimes and pursue global captures like the United States, the international community would completely regress to a state of the jungle.

The deeper issue is that this legal logic has a structural isomorphism with the "COIN (Counterinsurgency) Strategy" the United States promotes globally. The core of counterinsurgency theory is not to destroy the enemy, but to "win hearts and minds," which means isolating and dismantling the social foundation of the insurgency by establishing legitimacy. In U.S. strategic discourse, the global order itself is understood as an ongoing counterinsurgency war, where the United States and its allies represent the "legitimate government" and those countries refusing to accept the U.S.-led order are "insurgents." Military interventions, economic sanctions, regime changes, and judicial prosecutions against these countries are all incorporated into the scope of "full-spectrum counterinsurgency operations," the goal of which is not simply to eliminate the enemy, but to win the support of the international community through the appearance of legal procedures, thereby isolating the target regime. The indictment in the Maduro case is a typical manifestation of this strategy: the United States does not need to directly send troops to overthrow the Maduro regime but only needs to characterize him as a criminal through judicial procedures, thereby denying the legitimacy of his rule at the legal level and providing a "rule of law" cloak for subsequent regime change actions.

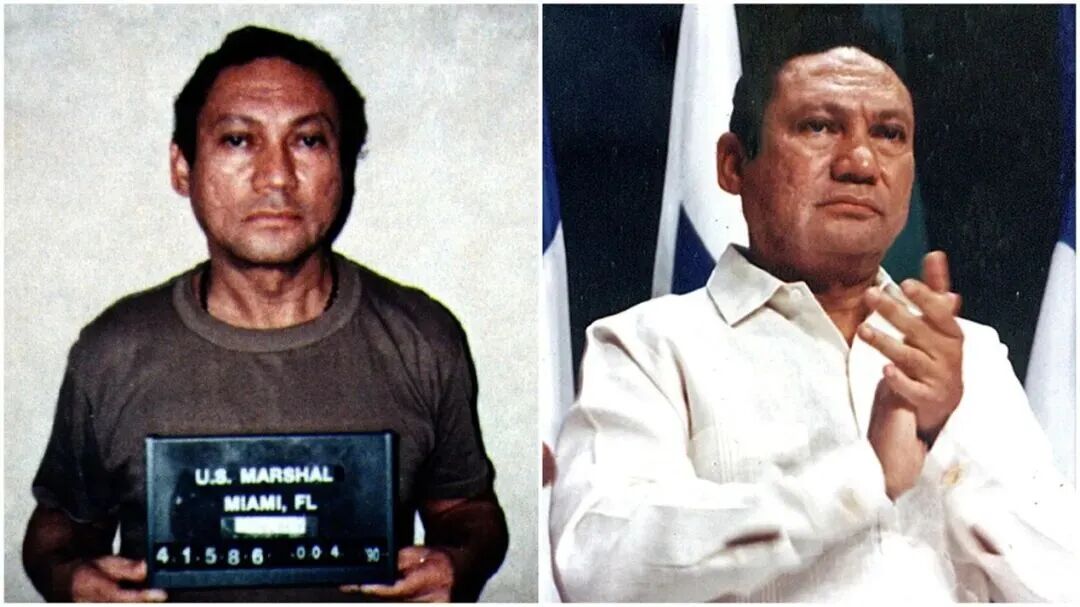

This operation of transforming international political conflicts into domestic criminal cases has a long tradition in U.S. legal practice. From the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama to arrest Noriega (Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno), to the trial of Saddam Hussein after the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the warrants for Libya's Gaddafi and Syria's Assad, the United States has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to package "regime change" as a "law enforcement operation." The key to this packaging is to downgrade the target figure from a political leader to a criminal offender, thereby granting military intervention a certain "legal legitimacy." In the Noriega case, one of the reasons for the U.S. invasion of Panama was to "arrest a drug trafficker indicted by a U.S. court," despite Noriega being the de facto ruler of Panama at the time. When trial proceedings began, the U.S. court explicitly refused to recognize Noriega's head-of-state immunity on the grounds that his regime was "not recognized as a legitimate government by the United States." This ruling set a dangerous precedent: a country can circumvent international law provisions on sovereign immunity by unilaterally refusing to recognize the legitimacy of another country's government.

Image Captions: Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno (Spanish: Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno; February 11, 1934 – May 29, 2017), the Supreme Leader of Panama (1983–1989) and a U.S. federal prisoner (1992–2007).

The specificity of the Maduro case lies in the fact that the Venezuelan government has not been in a state of military defeat or regime collapse, as were Noriega or Saddam. Maduro still firmly controls the state apparatus of Venezuela, and the Venezuelan military, police, and judicial systems remain loyal to him. In this situation, arresting Maduro, whether through secret operations or extradition procedures, inevitably constitutes a serious violation of Venezuelan sovereignty. However, in the U.S. legal narrative, this violation is reformulated as "cross-border law enforcement cooperation." The U.S. Department of Justice will likely claim that Maduro’s arrest was accomplished with the cooperation of the "true representatives of the Venezuelan people"—namely, the opposition government recognized by the United States—and thus does not constitute a violation of Venezuelan sovereignty. The absurdity of this argument is that it transforms sovereignty from an objective legal fact into a subjective political judgment: only those governments recognized by the United States possess sovereignty, while governments not recognized by the United States are not viewed as sovereigns even if they actually control the state apparatus.

This logic is supported at the technical legal level by the selective application of "State Succession" and "Recognition of Government" theories by the United States. In international law, there are traditionally two standards for whether a new regime should be recognized as a legitimate government: the "effective control principle" and the "legitimacy principle." The former emphasizes actual control capability, while the latter emphasizes the source of governing legitimacy. The United States flexibly chooses between these two standards: when a U.S.-supported regime has weak actual control, the U.S. invokes the "legitimacy principle" to maintain its recognition; when a regime opposed by the U.S. effectively controls territory but does not conform to U.S. values, the U.S. invokes the "legitimacy principle" to deny recognition. Regarding Venezuela, the United States has recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the "interim president" since 2019, despite Guaidó never having actually controlled any territory or government institutions in Venezuela. This recognition is based purely on the U.S. unilateral interpretation of "democratic legitimacy," completely disregarding the basic rules of international law regarding the recognition of governments.

More noteworthy is the U.S. appropriation of "Transitional Justice" theory during this process. Transitional justice originally referred to handling historical legacy issues through trials, truth commissions, and reparations after a regime change or conflict has ended, with the premise that the old regime has fallen or the conflict has concluded. However, the U.S. counterinsurgency law logic advances transitional justice to the time when the conflict is ongoing: while the Maduro regime has not yet fallen, judicial procedures are initiated to liquidate it, with the aim of using legal means to accelerate regime change. The core of this "turbulent transition" is that transitional justice is no longer a passive response after a conflict, but a part of the conflict itself—an active tool used to dismantle the legitimacy of a hostile regime, divide its supporters, and create a legal basis for military intervention or regime change. In this sense, the indictment of Maduro is not to achieve justice but to achieve regime change; it is not law constraining politics, but law serving politics.

This practice of instrumentalizing the law has explicit theoretical support in the U.S. counterinsurgency manuals. The 2012 edition of the Counterinsurgency Manual emphasizes that law is not an external constraint in counterinsurgency but the "link connecting the people with the political order" and a "mechanism through which the government gains legitimacy and makes the people assume obligations." The manual explicitly states that victory in counterinsurgency does not depend on how many enemies are eliminated, but on whether public support can be gained through law, governance, and public services. At the global level, this means the U.S. needs to shape the legitimacy of its actions through international legal procedures—even those initiated unilaterally—to defeat opponents in "legitimacy competition." The symbolic significance of indicting Maduro far outweighs its practical significance: even if Maduro is never extradited to the United States for trial, the indictment itself has already characterized him as a criminal in the discourse of law, thereby weakening the legitimacy of the Venezuelan government in the international community and providing a "legal basis" for countries supporting U.S. policy to refuse to deal with the Maduro government.

This legal strategy involves another key element: the dual manipulation of the concept of "legitimacy." In U.S. theoretical discourse, legitimacy is divided into "legal legitimacy" and "sociological legitimacy": the former comes from procedural justice, and the latter from popular identity. In domestic counterinsurgency operations, both types of legitimacy must be maintained simultaneously, because relying solely on procedural justice while losing popular support leads to strategic failure. However, at the international level, the United States cleverly exploits the tension between these two. When U.S. actions comply with international law procedures, it emphasizes legal legitimacy; when U.S. actions violate international law but might gain support from some countries or populations, it emphasizes sociological legitimacy. In the Maduro case, the act of indictment clearly lacks legal legitimacy in the sense of international law—there is no UN authorization, no basis in international law for universal jurisdiction, and it is purely a unilateral expansion of U.S. domestic law—but the United States attempts to gain sociological legitimacy by portraying the Maduro government as "dictatorial, corrupt, and drug-trafficking," thereby defending its actions in international public opinion.

The danger of this manipulation of legitimacy is that it creates a "normalization of the state of exception." In Carl Schmitt's political theology, the sovereign is defined as "he who decides on the exception." Through its counterinsurgency law logic, the United States positions itself as the sovereign of the global order: it can decide which countries are in a "normal" state and thus subject to conventional international law rules, and which are in an "exception" state and thus can be treated as insurgent organizations. This decision-making power does not need to pass through any international procedure, does not require UN Security Council authorization, and does not need a judgment from the International Court of Justice, but depends purely on the unilateral assessment of the U.S. executive branch. Once a country is designated by the United States as a "rogue state" or "criminal regime," all actions against it—be they military strikes, economic blockades, or judicial prosecutions—are automatically exempted from the constraints of international law, as these actions are redefined as "law enforcement" rather than "war," and "counterinsurgency" rather than "aggression."

The most extreme manifestation of this legal logic is the U.S. creative application of the "enemy combatant" concept. In the traditional law of war, captured combatants are either prisoners of war protected by the Geneva Conventions or criminals protected by criminal procedure. However, the United States created this third category of "enemy combatant" in the War on Terror, who enjoy neither prisoner-of-war treatment nor the rights of criminal defendants and can be detained indefinitely without trial. The jurisprudential basis of this concept is precisely to characterize the War on Terror as a hybrid state: it is war, so lethal force can be used and long-term detention practiced, yet it is law enforcement, so it is not subject to the rules of the law of war regarding prisoner-of-war treatment. The Maduro case follows the same logic: Maduro is neither a head of a belligerent state, thus not enjoying wartime immunity, nor an ordinary foreign citizen, thus not protected by sovereign immunity, but a "leader of a criminal organization" who can be globally pursued like Osama bin Laden or Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

From a broader historical perspective, this U.S. legal system represents a new mode of imperial rule. Traditional empires maintained their hegemony through direct territorial occupation and colonial rule, whereas the American empire achieves global governance through the hegemony of legal discourse. It does not need to station governors in every country but only needs to control the interpretation of international legal discourse to decide which countries' sovereignty should be respected and which should be ignored; which governments' legitimacy should be recognized and which should be characterized as criminal syndicates. The ingenuity of this imperial mode lies in preserving the form of sovereign equality while establishing a hierarchical global order in substance: those countries that accept U.S. rules enjoy full sovereignty, while those that challenge U.S. rules are downgraded to "insurgents" whose leaders can be globally wanted as criminals.

The maintenance of this order relies on a key legal fiction: the existence of an "international community" that transcends the sovereignty of various countries, with the United States as the spokesperson for the will of this "international community." In U.S. legal rhetoric, the indictment against Maduro is not a unilateral U.S. action but a collective strike by the "international community" against "transnational crime." This rhetorical strategy attempts to package U.S. special interests as universal interests and U.S. unilateral actions as multilateral cooperation. However, the problem is that the so-called "international community" does not have a unified will but is merely an anarchic system composed of countries with vastly different strengths. The reason the United States can speak on behalf of the "international community" is not that it has gained authorization from other countries, but purely because it possesses overwhelming military and economic power. This legal hegemony based on strength is fundamentally antithetical to the principle of sovereign equality in the Westphalian system.

A more profound contradiction is that the United States promotes the "rule of law" and "democracy" globally while practicing the crudest "might makes right" at the international level. The United States demands that other countries respect judicial independence, abide by procedural justice, and accept the constraints of international law, yet it can unilaterally decide which international law rules apply to itself, can refuse to join the International Criminal Court, and can authorize the president through the American Service-Members' Protection Act to use "all means necessary" to rescue any American detained by an international court. This double standard is particularly evident in the Maduro case: the United States requires Venezuela to submit to the jurisdiction of U.S. courts but will never accept the jurisdiction of any international court over the U.S. president or high-ranking officials. This asymmetry reveals the essence of U.S. legal imperialism: law is not for constraining the strong, but a tool used by the strong to constrain the weak.

From Venezuela's perspective, the Maduro case represents the complete collapse of the principle of sovereignty. If a country's head of state can be globally wanted because of an indictment by a U.S. domestic court, what meaning does sovereignty still have? If the United States can unilaterally decide which government is legitimate and which should be overthrown, what binding force do the provisions of the UN Charter regarding non-interference in internal affairs still possess? If U.S. judicial jurisdiction can be extended without limit to anywhere in the world, how can other countries maintain their own legal orders? These questions concern not only Venezuela but all countries unwilling to completely submit to the U.S. will. Today, the United States can indict Maduro in the name of "drug trafficking," tomorrow it can indict leaders of other countries in the name of "human rights violations," and the day after it can launch "law enforcement operations" against any regime it dislikes in the name of "threatening U.S. security."

The danger of this legal warfare lies not only in its violation of the sovereignty of individual countries but also in its fundamental undermining of the foundation of the international legal order. The survival of international law depends on the common recognition and observance of basic rules by all countries, the most core of which are sovereign equality, non-interference in internal affairs, and the prohibition of the threat of force. When the most powerful country in the world openly ignores these rules and rationalizes its violations through legal techniques, what reason do other countries have to continue following these rules? U.S. practices are effectively encouraging all capable countries to follow suit: Can China invoke the "Anti-Secession Law" to issue global arrest warrants for leaders of the Taiwan region? Can Russia invoke the principle of "protecting its citizens" to launch judicial prosecutions against the Ukrainian president? If every major power extends its domestic jurisdiction globally like the United States, the international community will fall into a total legal war, and the final result can only be the return of the law of the jungle.

Image Captions: International Society: Rule of Law or Jungle?

The Maduro case is therefore not just a specific legal event but a symbolic turning point: it marks the complete abandonment by the United States of efforts to maintain international order through multilateral mechanisms, turning instead to unilateral legal hegemony to advance its global strategy. The root of this shift lies in the relative decline of U.S. power and the trend toward a multipolar international system. When the United States finds it increasingly difficult to obtain authorization through the UN Security Council or other multilateral mechanisms, it chooses to bypass them and directly achieve its strategic goals through its own legal system. This strategy might be effective in the short term, but in the long term, it will accelerate the disintegration of the international legal order and the fragmentation of global governance. As more countries realize that international law cannot protect them from the encroachments of power, they can only seek self-preservation by developing military strength, establishing exclusive alliances, or conducting preemptive strikes—precisely the choice made by European countries before World War I and the direct cause of that catastrophic conflict.

(All images were provided by the original author and obtained from publicly available sources.)